Super Brain Blog: Season 4 Episode 4

Super Brain Blog – Season 4 Episode 4

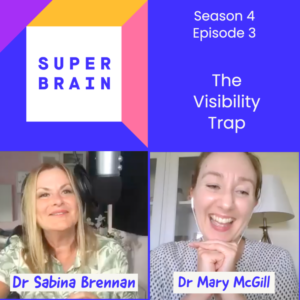

Selfie-taking and self-esteem with Dr Mary McGill

Become a Patron

Listen and Subscribe:

Trailer

Topics

- 01:01 – Dehumanisation and the darker side of humanity

- 03:52 – Social media exposes our biases

- 07:07 – Social media is designed to distort

- 10:31 – The Kardashian Industrial Complex

- 16:53 – The Instagram Look

- 20:29 – Selfie-taking, self-esteem, mood and body shame

- 24:00 – The girlfriend gaze

- 27:02 – Censoring the female form

- 33:37 – Cancel Culture

- 38:11 – Stoicism

Links

The Visibility Trap by Dr Mary McGill

Guest Bio

Dr Mary McGill is a media studies lecturer and journalist based in Ireland. Described by the Sunday Business Post as “essential reading”, her first book, The Visibility Trap: Sexism, Surveillance and Social Media, was published by New Island Books in July 2021. Her research explores the complex ways young women engage with selfie-practices and how the rise of social media is changing the way we see ourselves online and beyond. She is a former Hardiman Scholar at the National University of Ireland, Galway, and a regular contributor and writer in the Irish media.

Over to You

Do you admire the Kardashians? Were you aware that social media knowingly gives more visibility to thin white female forms? Would you like to see more diverse body types on social media.

What do you think of cancel culture? Do you think we could create more balanced, more empathetic platforms for social interaction with opportunities for more social integration across cultures and with holders of opposing opinions.

I really would love to hear your thoughts.

Don’t forget to share the episode on your social media.

Transcript

Sabina Brennan 00:01

Hello, and welcome to Super brain the podcast for everyone with a brain. My name is Sabina Brennan. And thank you so much for tuning in to part two of my conversation with Dr. Mary McGill. If you haven’t yet listened to last week’s episode, I suggest you press pause, go back, have a listen. And then come back and listen to this part two of my conversation with my fascinating guest, Dr. Mary McGill, author of The Visibility Trap – sexism, surveillance and social media.

Sabina Brennan 00:36

I had another guest on in season one. And she was publicly shamed in social media A journalist because she wrote a piece about ‘how do we find the balance between fat shaming and encouraging people to lose weight for health benefits and whatever?’. But before she knew it, she was vilified globally, lost a job, all the rest. And you have plenty of stories in the book about those things.

Mary McGill 01:01

One thing I always try on an individual level, knowing how these technologies operate. I mean, I think what you’re describing there is various processes of dehumanisation, Dehumanisation, not just directed at other people, but dehumanisation of yourself. Because when you fail to recognise somebody else’s humanity, you’re actually diminishing your own. And I think very often, we’re not encouraged to have humility in these spaces, we’re encouraged to go out all guns blazing. And I think that doesn’t leave room for reflection that doesn’t leave room for nuances. And sometimes I’ll be honest with you, it kind of scares me because if history tells us anything, it is that people can do terrible things when they believe that they are right. You know, how do you know that what you’re saying is correct. If you can’t, even on a very basic level, even privately, engage honestly, with counter opinions, and look it, if those counter opinions are abhorrent that’s gonna be pretty obvious. But the counter opinions are, of course, that I’m talking about are the ones that actually will give you pause for thought. Or God, dare I say it make you change your mind?

Sabina Brennan 02:06

Yeah.

Mary McGill 02:07

So I think that that space for reflection and thought and dialogue, in theory, these should be flourishing like never before

Mary McGill 02:17

But that is not what that what happened and whatever our perspectives that value that principle, we all should be concerned about that, right? Because we know human history tells us that that shutting down and that bad faith, and that, you know, kind of binary thinking with other human beings is profoundly dangerous. And when I’m thinking about the darker side of all of this, I mean, that is what I’m very, very worried about, but it is stirring up forces that never quite go away. And that by the way, can I just say are not about ‘us and them’, every human being has darkness in them. And we don’t like talking about that, right? Because otherwise, how could horrible things have happened are happening now and happen throughout time, you know, the human mind and the human heart are complicated things. And of course, these technologies understand that, but again, and to go back to what I said earlier on, very often, instead of operating from a place that would temper down on those instincts and boost better instincts, they seem to trade on whatever instinct is going because all attention is engagement, engagement can be created, converted into a metric, which in turn, can be converted into cash. So it doesn’t matter if that engagement or attention is destroying someone’s life or destroying democracy, it’s all the same, because it all goes into the same cash pile. I think that is, if you want to call it an experiment, shall we say, I think we’re beginning to see now that we need to take the temperature down and to rethink. And I think that, of course, involves governments and laws, but it also involves us as individuals and how we approach these spaces.

Sabina Brennan 02:17

Right.

Sabina Brennan 03:52

And I think, you know, as I’m thinking and talking through this, which is really what I love about the podcast medium is that I can read this book, and I have questions and things that I want to talk to you about and ask you questions. But what I’m loving particularly about this chat is I’m getting ideas from talking to you. This is what social media should have been and was intended for and was for a while, you know, collaboration ideas, exploring thoughts, thinking through Why is that happening? And I do particularly like podcasting for that because it’s a longer duration, you actually get to engage with people and explore and get to know people and get to discuss and you know, back and forth. You don’t always have to agree with each other but you can kind of explore, we have multiple biases, okay. Basically, when we talk about bias, people tend to think about racism and sexism, etc. Look, we have biases about ourselves, we have biases about absolutely every single thing. Essentially, all they are are the brain’s heuristics. So they’re just shortcuts. So the thinking brain uses the most energy so your brain is constantly trying to find ways to limit the use in a way…. to maximise the efficiency. So anything that we can give to the unconscious brain to do is helpful. It frees up the conscious brain for actually doing the things that allowed us evolve, inventing stuff, and engaging with people writing books, making art, literature, all those fabulous things that make us human. It’s like the reverse of evolution, that’s kind of what we’re at risk of happening here is because the social media and again, I’m thinking this off the cuff sort of thing, that social media is bypassing our rational thinking brain and operating on that. So it’s exposing our biases, our heuristics. And whilst they’re always there, in another situation, you have a chance to slow down and think rationally, because that keyboard is at the tip of your finger, you can go straight from that thought to that and expose those biases without realising that they are just heuristics and that your brain can be wrong, your brain does not see a reality, what you interpret as the reality is just that. It is your brain’s interpretation based on the data it has available. Now we all know that social media actually manipulates the data that is available to you. So you get biased data. So biased incoming data on top of internal biases means that you’re going to see a completely different reality to somebody else.So your and my reality and view of the world when it comes to gender or sexism is going to be entirely different to someone who is a sexist, or a racist or whatever. And they are going to believe that they are just as right and accurate, in the same way that we believe that we’re right and accurate. I think perhaps that’s why maybe social media has changed so rapidly recently, is that you used to be able to see everything and that’s access to data. But then social media decided it better and decided to feed us stuff it knows we like so then all you’re doing is creating bigots, racists, sexists.

Mary McGill 07:07

Yeah, I think what social media does, is distort. And I think that that distortion is often something that we’re not particularly aware of, because these are technologies that are frictionless to us. And they feel quite organic in our hands, right? I mean, I’m sure you’ve seen toddlers with iPods. And it almost seems kind of intuitive, right? I think on our behalf, there’s kind of an almost unthinking presumption that what manifests on our screen simply is right, we’re not encouraged to look.

Sabina Brennan 07:41

To think critically

Mary McGill 07:44

Yeah, And to consider what is going on, what are all the calculations that lead to you seeing your version of quote, unquote, online reality, or me seeing my version, quote, unquote, of online reality. And of course, that can be used in lots of ways, some people will become visible because of it, a lot of lot more people will be denied visibility online because of it. It’s also a convenient way for material that you would find annoying somehow making its way into your timeline. And of course, our minds are primed for negativity and will be drawn to the annoying thing, you know, and will dwell on that probably more than the most positive thing. But surely, that’s not a good… I mean, if if something’s been placed there just to get your attention, because attention is the most important thing, but it’s actually annoying you and just generally, you know, not really what you want to see, but it’s capturing your attention, nonetheless. Why do that? Well, because it creates attention, right, and the more attention is good attention is the metric that matters, right? So I think these technologies are designed to distort they are designed to amplify and amplify is another type of distortion. So it can feel like we’ll say, if you look, for example, at one of the studies that looked at the way ads on Facebook were used during the 2016 presidential election, what they found in one case was that the ad spend on this particular I think was pro Trump ads was about $100,000. Actually, not that much really in the grand scale of things, this misleading information, but that material had been shared over 100 million times on Facebook. That this is the issue, right? This is the amplification feeding into distortion, right? So you don’t actually need that many bad actors for them to have an outsized effect in these spaces, You know. And the vast majority of social media content quite often is produced by people. A small group of people in comparison to actually the amount of people who have an account, but the small group of people are just heavily online. So they’re the ones producing the vast majority of the content. But if you go to these platforms, and you assume that by logging on, you are getting some unfiltered version of reality or what people are thinking and feeling. I mean, you’re getting a slice of It, maybe something but you’re not getting the whole picture. And I think now more than ever, we need a broader sense of what people are thinking or feeling. And we need to be very careful about kind of falling into the distortions that Social Media presents. Because you know, when you’re in that space, the world has been distorted, you’re being distorted. You know, you just need to just be careful with it.

Sabina Brennan 10:26

There’s so many interesting chapters, there’s another one on influence, which just has incredible stuff in it.

Mary McGill 10:31

So what I write about in the book is something I call the Kardashian Industrial Complex. And it looks at the way the Kardashians have kind of… the surveillance that was inherent with a reality TV where they first made their splash in terms of the entertainment industry, but of course is inbuilt in social media. They understood and were very good at being responsive to that change. This notion of celebrity is ‘access all areas’, which happened there to a degree in programming from the 90s with the advent of reality television. But of course, it has kicked up a number of gears now with social media, and they embrace the surveillance, right, they commodify every aspect of their lives. They let cameras in,you know, everywhere, they were prophetic, and their ability to spot the earning power of something like Instagram, I mean, Instagram, when it started, I was purely, you know, photographs. And we didn’t have the notion of influencers as selling things to Instagram. You know, the Kardashians are one of the people who really understood the economic power of these platforms. They’ve also devised lifestyles and products, where the products are, you know, help to kind of deal with the spotlight of social media. So the makeup stuff and the underwear stuff, and the detoxes. And all of these things. You know, this is about achieving a certain look in this hyper visual culture where women are expected to want to be seen and to want to showcase their lives on these platforms. The Kardashian Industrial Complex, there’s not really much dissent involved, like the assumption is that this is what smart 21st century women do. They reproduce themselves in this way, they’re glossy, they’re in control. their femininity is something that they almost approach as like a brand. It’s something they do for themselves, or they do for their friends, almost as part of their career, their whole outlook. And when you talk to some young women about the Kardashians, they find them hugely inspiring for that reason, the fact that they are entrepreneurs, and they have managed to create this empire. And in the book, I’m really careful not to, although I’m very critical of them, I do take them seriously.

Sabina Brennan 12:30

No, absolutely.

Mary McGill 12:31

I think there’s a real snobbery, particularly when it comes perhaps to things that are seen as feminine, even though things like the fashion and beauty industry are worth billions upon billions, just the sport is but sports, you know…. we just get these double standards everywhere. Yeah. So the Kardashian phenomenon, it’s interesting in terms of how the media has changed over the last 20 years, it’s fascinating in terms of how consumption has changed over the last 20 years, it’s fascinating in terms of how celebrity has changed over the last 20 years, they have taken the visibility that is inherent to the media landscape. And they have built a brand around embracing that visibility, and this idea that you can take it and you can meet it and you can make yourself wealthy from it and make yourself desirable from it. And that you can be in control. And of course, that word quote unquote, empowered. And indeed for people at the very top of the food chain like the Kardashians, and you know, there are lots of other very, very successful influencer of that mould. Even though there are lots of different types of different ways of being an influencer. I’m talking about a very specific type of influencer in this respect. And they do of course, they’ve done incredibly well, from this new marketplace.

Sabina Brennan 13:42

If you measure that success by how much money they’ve made. I do think that is another cultural thing is that success does appear to be measured by how much money you have, so that you can purchase the lifestyle that they have. But in between all of that when you look at it, relationships aren’t working out. You know, for them, they still make money if they go for a divorce, you know, because that’s even more money coming in. But at the end of the day, I think what gets forgotten as well is aspiring to be like the Kardashians. Do you really want you know, in a way, it must be exhausting doing what they’re doing. They’re ‘on’ all the time.

Mary McGill 14:18

Well, I think they’re very savvy with like, everything that happens, the heartbreak, the divorces, everything else, everything gets absorbed into the brand and makes them even more relatable.

Sabina Brennan 14:26

Yeah,

Mary McGill 14:27

and this is no mean feat because these people are multimillionaires. So the idea of being relatable is that they do manage to a certain degree make that appeal to the very many people who follow them. My real sympathy lies with the people who don’t have anything like those resources, who are believing in this notion of this new economy that does work out for some people, just as it always has worked out for some people, but those people are generally you know, the one in the million, but you have, you know, people who desire to be content creators or influencers without that notoriety to back them up for those kinds of resources. They are working so hard. One young woman I interviewed for the book she said, you know, you’re your own everything your your writer, your manager, editor, everything. And I think again in being snooty and making assumptions about influencers and content creators and so on, completely ignores the reality of the work often work that is done by women because it tends to be in female dominated space. This is a new marketplace that has evolved, it has none of the security, none of the benefits of previous types of employment. And the vast majority people who are trying to make their way in it are not the Kardashians. So when the Kardashians are held up as this kind of visibility that these are what influencers are, you’re like, no, that’s a particular type. Yeah. But there’s a whole other world and worlds out there of people who are working so hard with very little support in a role that’s misunderstood a lot of the time. And it’s not easy.

Sabina Brennan 15:56

I would identify hugely with it I wouldn’t see myself as an influencer. But I am working in that gig economy. And in that way, and I suppose Yes, in some ways, I’m trying to have influence in a very different way, I’m not trying to influence you to buy makeup, I’m trying to influence you to take good care of your brain health and learn how to understand your brain health. And then of course, there are ways you know, I need to eat and make a living as well. But I understand you are everything. The thing and I think you pointed out in a way. And while they have done incredible things, they have not done these things alone, and they did not start from a baseline that you and I are at. They started from incredibly rich and public families. So you know, they will have teams of people posting this stuff and suggesting what needs to be done. And that’s kind of a deception. That’s dangerous. I think there’s a few things as well like that you touch on I think also in that chapter. And I do think that the Kardashian KIC.

Mary McGill 16:50

Yeah, Kardashian Industrial Complex. Yeah.

Sabina Brennan 16:53

But you talk about face tune, and all these various devices that people now have access to to create their public filtered image, which then actually results in, as you said, the Instagram look. So essentially, you’re making yourself more like others more the same. This uniformed vision, but that has huge knock on effects. In terms of like imposter syndrome, you know, you’re not really the person you’re presenting, wishing that You looked like you know…. Going to get plastic surgery to look like your face-tuned image of yourself, your self esteem, your depression, your not wanting to go online, unless you look your best, all those things that all of us experience, but they are very real detrimental effects. But the whole point is that the solutions that are being provided, are for, as you point out, problems that have been created by the solution providers. And so essentially, there’s just this roundabout that you’re on that actually, if we could just all step off it they go out of business. Like we are feeding the monster, and then giving the monster our money. That’s what I like about books like this. And I know people hate that word empowerment, but I don’t know of a good replacement. But knowledge is power. And if you understand these things, and I really do urge people to get the book, it really makes you think about how implicitly complicit you are in this terrible cycle

Mary McGill 18:18

that is really not good for women. When you begin to look at the literature, and you know, yourself this literature, hey, there’s still so much we don’t know, right? We’re still kind of digging through this material. But what’s really striking when it comes to comparison, culture, and fragmentation, and all of these things, is I suppose, perhaps, specificity. And what I mean by that is how we use these technologies matters. And what we bring to them matters. Because not everybody is going to feel the need for validation through something like a selfie. So why are some people more prone to needing that validation? Or perhaps in certain times, perhaps when they’re a bit younger, perhaps when they’re, you know, things are being tough, or whatever the case may be, I know that people can kind of take it or leave it. And I have seen this myself, just in research. And we’ll say talking with young women, that some people seem to have a kind of a natural ability to…, not that they’re not affected, but they’re better at realising it. Or been like ‘that made me feel bad. So I’m not going to do any more’ or ‘that made me feel bad. o I’m not going to use this platform’. But I like this platform. And I use it this way. So that’s what I’m going to do. For some people it seems to be that made me feel bad, but it also made me feel good. So I’m just going to keep doing it in the hope that it’s going to make me feel because the feeling good is worth about even though the bad is really bad. And I actually don’t like it at all.

Sabina Brennan 19:45

But that’s exactly how abusive relationships work,

Mary McGill 19:49

right? Yes, yes, yeah.

Sabina Brennan 19:51

If you’re in an abusive relationship, if that abuser is constantly bad to you, you may actually have a chance of surviving However, it’s the occasional good that they do to you, I’m so sorry …it’s only, cause I love you. And here’s this, this, this and this. And it’s that good moment that keeps the female, usually the female trapped in that abusive relationship. And now Yeah, that, again, is just understanding how human behaviour works and how human behaviour is reinforced. It’s intermittent reinforcement, and is one of the most difficult types of behaviour to disrupt.

Mary McGill 20:29

Yes, and that does not surprise me, that does not surprise me, at least, because when you go to the literature that we have on we’ll say, ‘selfie taking’ on body shame, and low self esteem and things like that, very often, the researchers will make a point of saying, you know, we find this, but one factor would be that people who present with these tendencies, they are more prone to compare themselves with others, right? So that the technology then is tapping into that vulnerability, you get this kind of, I suppose, feedback or loop effect, right? So when the technology might not necessarily have caused that vulnerability, it is certainly exploiting that vulnerability.

Sabina Brennan 21:09

Yes. And that’s awful.

Mary McGill 21:11

It’s awful. It is. Often when people when you work in this area, they’re like, does it cause is it caused? And you’re like, you know, maybe we’re too fixated on cause right?

Sabina Brennan 21:19

Oh, yeah, yeah,

Mary McGill 21:20

maybe what we need to be asking … I mean that that’s such a, you know, oh, it makes this happen. And you’re like, oh I dunno…. to say that conclusively about anything? It’s a big question to ask.

Sabina Brennan 21:31

Yeah, you really can’t, when it comes to the human condition, and the human brain and behaviour, singular causes really aren’t at play. They just aren’t, it is multiple causes, but also multiple contexts. So in one context, something happened might lead to something detrimental in another context, it won’t, even as a female, you know, we have to acknowledge the role that our brain and our body plays in terms of our behaviour and our vulnerabilities. Knowledge is power. It really is.

Mary McGill 22:02

Yeah, absolutely. And that’s one of the things I wanted to do with the brook and say in reference to, you know, research on the selfie, just having that self awareness to catch yourself, you know, there’s interesting research on the impacts of mood, depending on the type of selfie practice that you engage in. So if you’re taking selfies that are light hearted, that involve food, or you know, nice, sunsets or humorous, and if those are the type of selfies that you’re consuming as well, they’re probably not going to have a negative impact on your mood or your self-esteem. However, if you are taking the type of selfies and oriented around beauty practices, where there’s a high degree of self surveillance, and there’s a high degree of you know, judgment and being critical of other people selfies as well, and you are someone who was prone to comparison, then that is probably not going to do you a whole lot of good. But if you know that, and if you know, you can be like oh, you know, and you have the self awareness to catch yourself in the mood where you’re reaching for that… you’re looking at. And if that’s all it takes, to make you put your phone down or get a bit of distance. So that’s just not so much in your head. That I mean, I would be delighted with that. Because these technologies have overtaken our ability to build the kind of shorthand or common sense around them when it comes to use a lot of the time, unless you have the good fortune to be, you know, in academia or in research or wherever the case may be a lot of these ideas, they need to be hitting the people who they’re researching.

Sabina Brennan 23:30

They really do. Oh, yeah. And that’s one of the reasons I do what I do is that academia encourages publication in academic journals. And that’s why I love that you published your PhD, but then you publish this book for everyone else. And I almost feel that that actually should be almost a requirement in a way. I do feel it should be a requirement that research is made accessible, watching yourself watching other people trying to figure out how should I be How should I look? And actually, you have some line and I can’t remember where you actually evoke The Handmaiden.

Mary McGill 24:00

Oh, yeah, no, that’s a British researcher Alison Winch. Yeah, she talks about the girlfriend gaze being this kind of very female, very critical gaze. Being that the male gaze is Handmaiden.

Sabina Brennan 24:11

Yes, yes.

Mary McGill 24:12

And it is certainly in certain respects online in these very female spaces. Which Instagram can tend to be It is more grounded as a female gaze

Sabina Brennan 24:20

it’s other female. Yeah, yeah. And I have to say, like my experience across my life, and these are some of the things that I would feel uncomfortable saying, and but at least I can kind of qualify myself if we do it here that, in my experience, females are the ones who appear more critical of other females. Or it can feel like that whether it’s true or not, but it can certainly feel like that. Certainly, as a schoolgirl, and you do…. and I think that’s very relevant. You do speak of social media as being the schoolgirl. That place where you are trying to discover who you are, and you’re looking at other people and going Oh, do I want to be like her? Oh, actually, everybody seems to really like her but okay. I’ll kind of ignore the fact that she’s bitchy. But I’d like to look like her, you know. And it is that space where you are kind of vulnerable. And when it comes to perfect bodies, I don’t think that men, I think a new generation may be different those who’ve grown up with the Internet, and they’re subjected to porn and just all these perfect bodies, but certainly in my generation, and before that, men are less critical of the female form and are excited by or aroused by the female form. Even if it has cellulite, or an extra few pounds, it’s much more organic than the eight pack and the looking perfect. That’s certainly what it was. When I was there. I don’t know whether it’s actually changed, it could change. That’s where I get fearful. But I definitely assume it impacts on women and how they feel and how they would feel undressing in front of people and all the rest. Anyway, tell us a little bit about the Bodies chapter and what the social media actually does.

Mary McGill 26:01

Yes, one of the things that is a big selling point for something like Instagram, if you go to its about page is it’ll tell you that, you know, you can create yourself on your self expression, values, be seen all this good stuff that really appeals to us as human beings, because we’re like, oh, yeah, I like the idea of being seen. And like the idea of creating myself, This all sounds like a lot of fun. We love to look as human beings, we’re very visually driven. We love images. And so you know, that’s all to the good. And in practice, though, not everybody gets to be seen in the same way. And that’s what the bodies chapter looks at, you know, so the likes of the Kardashians will get a high degree of visibility always, even when they come very, very close to breaking the terms of service. For people who don’t have that kind of following or for people who were challenging, we’ll say, traditional understandings of the female body just as an example, they will find themselves quite often censored, they may have their account taken away from them, they may have their images taken down.

Sabina Brennan 27:02

There’s two fantastic examples. If you can explain the image that you’re referring to with Kim Kardashian, what she was attempting to emulate. Yeah, and then there are a couple of them that come to mind. So there’s the woman with the bikini.

Mary McGill 27:13

Yeah, yeah.

Sabina Brennan 27:14

And then also, there’s one about… and this is where moderators come in, they’re really striking stories.

Mary McGill 27:21

They really are. As soon as last summer Noam, I hope I’m pronouncing her name correctly, she’s a very high profile and black British body positivity activist, caught up a series of images very beautiful images of herself on Instagram, and she was holding her chest with her arms, but there was no sign of the dreaded female nipple, which is not permitted on Instagram. Just so you know, for anybody who’s thinking about getting their nips out on Instagram. If you’re a woman,

Sabina Brennan 27:48

if you’re a woman, if you’re a man, you can have your nipples.

Mary McGill 27:51

Yeah, exactly. So this was an image I think I described in the book is kind of one of quite self acceptance and contemplation. It was very nicely done. aesthetically very beautiful. But it was taken down. It was taken down repeatedly over and over again. And both the blogger and the photographer who took it were just aghast, as were the people who were following what was happening online. Because highly sexual images of slim, Caucasian women are all over Instagram, and they are not removed and

Sabina Brennan 28:21

I get them.

Mary McGill 28:23

I know, yeah, we all get them and you kind of like us. So around the same time that this was playing out, Kylie Jenner had put up an image of herself and were also topless, whether I’m across her chest, it was deliberately provocative. You know, it was a very sexualised image.

Sabina Brennan 28:37

Yeah. Whereas the other one was a celebration just of, you know,

Mary McGill 28:41

body confidence

Sabina Brennan 28:42

no innuendo nothing. It’s just, you know, I’m sitting here and this is how I look, this is me and I’m okay. Yeah,

Mary McGill 28:50

this is me. And, you know, an important image because we’re not used to seeing women, particularly not used to seeing women outside this stifling normal, skinny whiteness embracing themselves like that. So Kylie Jenner was not even a thing, you know, everything else. But because this blogger had such a following, she was able to kind of draw attention to the fact that she had been… her images had been taken down and it became a thing and the newspapers in the UK picked it up, it became an international news story. And eventually, I think Instagram, the images were reinstated, they then changed their moderation policy to kind of add a bit of nuance around the fact that just because a woman is holding a breast does not necessarily mean that it’s sexual, right.

Sabina Brennan 29:30

I think what it was was that, for some people who aren’t aware, and that’s a whole other podcast, talk about it, as well as there are people who moderate content and you know, they can be moderating violent content, obscene content, etc. Not a very nice job, but they have rules and guidelines. So the rule in this instance, the reason hers was taken down was that apparently, you can embrace your breasts to hide them and to be you could describe it in so many different ways. Sexual, provocative, coquettish, or actually just playing Yeah, abiding by the rules, I can’t show my nipples on Instagram. The reason hers was taken down was apparently, if you move your arms to hold your breasts in a way that looks like you’re squeezing them, that is considered sexual. And of course, if this woman actually is different to, like, it’s an awful lot harder to wrap your arms around the size 42 bust or a 40 bust, than it is around the 32 bust without squeezing or whatever. But that was the judgment. And they changed that. And I think as you pointed to there, that woman had a big enough following and profile to highlight that issue. But most of us are unaware that we are being fed just one body type, and it is white

Mary McGill 30:42

and also just as well, just to say, yeah, and also the strength of character and the bravery. Because Yeah, not everybody has that energy within them to fight that was taking energy out of her career, you know, that was taking energy out of her, you know, day to day to live her life. And she did get support. And she had … she had, you know, a sizeable platform, and she did make change and all the rest of us. But throughout the book, you’re constantly meeting people who have had to fight because they have found themselves at the sharp end of these technologies. That’s not a situation ideally, women should be finding themselves in, but they are.

Sabina Brennan 31:16

But I think it shows us it’s back to gosh, you know, in some ways, even across my lifespan, things have changed and moved on. And you know, you didn’t used to be able to talk publicly about your periods or anything like that. And things have moved on. But then in other ways, they’ve moved backwards or done full circles, but basically as Lisa McInerney said, different perfumes, same shit. Basically, it is that there is one acceptable type of female body. And there’s one story in there where that really made a jump out to me. And that was someone showed a photograph of herself in her bikini with some of her pubes escaping out

Mary McGill 31:55

Ah yes

Sabina Brennan 31:56

and it was taken down.

Mary McGill 31:59

Petra Collins. it was just a picture. I’m I say if it’s her

Sabina Brennan 32:03

horrific reasons behind it

Mary McGill 32:03

When I say it was a picture of her crotch, I don’t mean that in any sexual way whatsoever. It was just, she’s an artist, you know, she was. So it was it was a picture of her in actually very sensible blue knickers that has to be said there was nothing remotely sexual about it. But it showed just along the trim of her knickers, it showed pubic hair,

Sabina Brennan 32:22

which is where pubic hair resides.

Mary McGill 32:25

I mean, shock and horror. There you go. And it caused… you know, again, was taken down, her account was closed. And yet these images of bodies that are far more sexualised, with far less clothing are allowed to circulate and are given such a high degree of visibility. And it’s like, what is so shocking about pubic hair? And specifically pubic hair that’s on a woman’s body? Right? You know, there’s almost like, these technologies are so progressive, or that’s what they sell themselves as, but the cultural ideas that inform them

Sabina Brennan 32:57

Oh Yeah,

Mary McGill 32:58

still have this Puritanism in them.

Sabina Brennan 33:00

Yeah, absolutely.

Mary McGill 33:01

Like, you’re free to represent yourself. But actually, you’re only free to represent yourself within quite defined parameters that can be very tricky to interpret. There’s not a whole lot of transparency until you find yourself up against them. Again, and again, in the Bodies chapter you hear from women who were like, and then you know, this was said to them you know… So this idea, again, to go back to that notion of control, they have control, the platform’s have control, absolutely, they will give you a degree of control, but your control will never ever, ever supersede theirs, they have the ultimate say,

Sabina Brennan 33:37

I think in one way it can. And that is you have control to step back and walk away from it. And that’s very hard to do. And it’s something that I’m going to kind of wrestle with, I suppose I have been doing it in more recent years in that I tend to limit my interaction on social media, actually, to my work or stuff that’s relevant, and then maybe my dogs. So it’s kind of pretty innocuous, because I’ve realised that actually, it’s not the right place or forum for the kind of nuanced, intelligent conversation. And I have to say, so we’ve been talking here about how, in a way, women are impacted by social media, but I think also and it’s a trend that I don’t like either, is that then it’s not just men who engage in the nasty, unfiltered behaviour. And I think this is problematic because I think it puts the cause of women backwards, is women behaving in that cancel culture that refusing to have a conversation, refusing to try and find some way forwards just the finger point, they are witch hunts, and I think what has made them even worse is they’re witch hunts of women, by women. And that seems like a particularly nasty form of witch hunting, But I do believe they are our modern day witch hunts. We have not not changed and it’s now become that place where There was the public stocks for the public shaming, etc. That’s it. But at least back then, if you were publicly shamed, you could leave and go to another village, this is global, there is nowhere to go and hide from these kinds of public shaming. It’s pretty horrific. And such a shame, because it could be this incredible tool. And it is an incredible tool. And I’ve had lots of very positive things come out of my use of social media. I think a lot of people are aware, because it’s very obvious that they are being listened to and watched by the technology itself, I keep getting a picture of actually this chair that I’m sitting on. I googled something and saw oh look that chair, my chair back again, and every time I log on, now, I’m just getting that chair, and it comes up because I clicked it. And obviously didn’t say no cookies, or whatever. So we know that our behaviour is being monitored in that way. But I don’t believe that. And I think people understand that opinions and certain posts are being filtered. But I don’t believe that women understand that the type of women that you see, in terms of body type and visual and ethnicity. I don’t believe that people realise that that is being manipulated. And I think that was one of the kind of big scary bits from the book. It’s not a horror story. It’s a very empowering book to use that phrase again. But if you can think of another way to say that I’m all ears. It’s fantastic. Thank you so much. Thank you, Sabina, anyone listening, get the book. It’s full of this fascinating stuff It’s called The Visibility Trap, sexism, surveillance and social media. And it’s by Mary McGill. And she just says Mary McGill, as opposed to Dr. Mary McGill. Or Mary McGill. PhD. The way I look at those letters that I have after my name is they’re just and I think, that’s all they really mean is they point to the fact that actually, you know, you have studied this, you’re just not randomly. And I think that’s another knock on effect. It has bled into publishing, influencers are being asked to write books, because of their following because it means sales. But that’s another form of filtering. That doesn’t happen that should happen is that when you filter through, anybody is allowed to give advice or say stuff. And often that involves the purchase of, for example, in my case, I’m looking at people advising people to buy supplements that are great for memory, or there’s no scientific research to say that, and yet they’re allowed kind of put that there anyway, you see, we could talk forever, because there’s just so many things and so much there. Do you have plans to write another book?

Mary McGill 37:41

I would like to you

Sabina Brennan 37:42

I know you’ve only just done this. Yeah, yeah. But you’d like the process?

Mary McGill 37:46

Yes. Yes, I do. I would like to Yeah, definitely. Yeah, I

Sabina Brennan 37:49

think even with this, even some of the topics within this could be expanded. But I also think there’s going to be more and more and I’m sure there was more bits that you would have liked to put in, you couldn’t put it in in terms of, you know, page numbers, etc. So I like to finish by asking my guests to offer a tip on surviving and are thriving in life.

Mary McGill 38:11

Oh, gosh, tip for surviving and are thriving in life. I have found myself over the last while ehh returning to a lot of very old things. And by old I mean, in terms of human history of human civilisation. I’m very interested in the stoic, stoic philosophy. And I would recommend anybody if they I think we live in a highly emotional age. And there’s nothing wrong with emotion. And but how you deal with it is really important. And I think the stoics offer some really interesting ways of thinking about the role of emotion in our lives. And I think over the last year, a way of thinking and a book that I have found a lot of wisdom and confidence in is a book from 1945 by a man called Albert Camus It’s called The Plague. And bear with me. The plague is set in Algiers in a town where there is an outbreak of the bubonic plague. And it follows a doctor who remains in the town to treat patients. So it works really powerfully as a narrative. But Camus also developed the notion of the plague as part of his philosophy, which is called absurdism, right, that the absurdity of life, which sounds nihilistic, but it’s not at all. And Camus says about The Plague, is that plagues force us to see the fragility of life, but fragility is all around us all the time. We’re just really good at distracting ourselves from that and thinking that we’re the ones in control, when the reality is that life can end or be turned upside down at any point and that is the metaphor of The plague. And at one stage, one of the doctors assisting him asked him, you know, how do you cope with that? Like, how do you cope with all this suffering and you know, and he just says, “You know, I do my work. And we go through it.” And I think that’s what we do with human beings, there is no way but through that you just kind of have to accept the plague as a condition of our existence, and go through,

Sabina Brennan 40:26

I totally hear what you’re saying, and obviously it will resonate for people because we’re living through it another plague. But it’s interesting what you say about the stoics and emotions, you know, I think it’s probably that the pendulum has swung too far. One way, so there’s this stoic, putting on the brave face thing. And you know, for years, we’ve heard about, oh, you, you’re not in touch with your emotions, get in touch with your emotions. But now, I think it’s probably swung too far the other way. And it’s not always good to let your emotions rule your behaviour. In fact, you know, in a way, emotions are the results of your thinking as well. And I suppose really, in a sense, what you’re saying is just do it, just live it, you have much more control and much less control than you think. So the big stuff, an awful lot of it, we have no control over it. So you just have to live through it but actually how you live through it, and how you respond to it. And what you do on a day to day level, you have huge amounts of control, huge amounts of control. And that’s how you think how you behave. And even how you feel you have much more control, those things don’t just happen, your brain and you and your behaviour are making things happen. And so you know, if they’re not working, you can switch them up and change. That’s fascinating. I may have a little look at that book. It’s always nice to get those kinds of tips, but the main book to consider folks is The Visibility Trap. It’s a fantastic read. My name is Sabina Brennan, and you’ve been listening to Super Brain the podcast for everyone with a brain. Super brain is a labor of love born of a desire to empower people to use their brain to thrive in life and attain their true potential. Please help me to reach as many people as possible by sharing this episode, or by simply liking or rating the show. Imagine if we could get to a million downloads by word of mouth alone. I believe it’s possible. I believe that great things happen when lots of people do little things. So you really can help to achieve this ambitious dream to get a million downloads. Oh, and don’t forget to subscribe to Super Brain that helps too. Visit sabinabrennan.ie. for additional content, including images and videos related to this episode and a transcript of the show. Follow me on Instagram @SabinaBrennan and on Twitter at @Sabina_brennan. I am grateful as always, to my exceptional editor Emily Burke, to my fascinating guests and to my listeners. Thank you for tuning in.

people, book, images, women, instagram, social media, brain, influencers, visibility, female, technologies, Kardashians, life, plague, thinking, encouraged, terms, body, selfie, changed